- Equity Shift

- Posts

- How (And When) to Raise Money if You’re Pre-revenue

How (And When) to Raise Money if You’re Pre-revenue

Heads up: you probably shouldn’t. But if you must, here’s a guide.

Find out why 1M+ professionals read Superhuman AI daily.

In 2 years you will be working for AI

Or an AI will be working for you

Here's how you can future-proof yourself:

Join the Superhuman AI newsletter – read by 1M+ people at top companies

Master AI tools, tutorials, and news in just 3 minutes a day

Become 10X more productive using AI

Join 1,000,000+ pros at companies like Google, Meta, and Amazon that are using AI to get ahead.

One of the most common questions I receive from founders is about how or if they can raise VC if they’re pre-revenue.

A screenshot of a DM I got from a founder TWO DAYS before I hit publish on this newsletter.

My usual response is harsh but honest: Get revenue first.

I know that's not what founders want to hear, but it’s true.

Most of us are average founders.

By average, I mean that to VCs, there’s nothing on our personal resumes (such as a Stanford CS degree) or on our company’s profile (like a YC W24 label) that will immediately capture their interest. For that reason, you need another way to get investor attention, and having revenue is an excellent way to do that.

With that being said, some circumstances require you to have capital before you can make money. And although these cases are rare, if you are confident that you need to raise money before you can start making money, this one's for you.

When It Actually Makes Sense to Raise Pre-Revenue

Before we dive into the tactical methods, let's determine whether you're actually in the small percentage of founders who genuinely need to raise capital before generating revenue.

There are three main categories of companies that need to raise funds before they can generate revenue:

Capital-intensive businesses

Think Rivian, the electric car company.

They had to raise billions of dollars before they could even get one car available for purchase.

If you're building hardware, developing biotech solutions, or creating anything that requires significant upfront manufacturing or R&D costs, you fall into this category.

Network effect businesses

Consider Uber.

Sure, Uber could have been a decent company if it had just established itself as a ride-share business in San Francisco, but it was clear from the beginning that the investors and founders had a big vision. That vision could only be achieved if they had loads of VC money to pour into:

subsidizing the rides, and

growing the driver base quickly through advertising and joining bonuses.

Regulatory requirements

Enter Coinbase.

Companies that need to adhere to complex regulatory standards require legal support and counsel upfront, and none of that is cheap. They were the first company in the crypto space, entering when many of the laws were still undefined. The founder, Brian Armstrong, recognized that regulations surrounding crypto would change rapidly, and to stay ahead, he had to establish frameworks for consistently updating and maintaining compliance. For that reason, Coinbase probably (we can’t be 100% sure because it’s not public information) raised money before they made any.

It's Really About Your Vision

What’s interesting about these cases is that, except for capital-intensive businesses like Rivian, whether you think you need money pre-revenue really depends on what vision you have for your company.

The founders of Uber and Coinbase were determined to build massive, category-defining companies from the beginning. They were willing to raise money pre-revenue because any revenue they generated early on wouldn't be meaningful enough for the business they envisioned.

So the core question you need to ask yourself is: What type of business are you trying to build?

Are you truly trying to build something game-changing? Or are you okay with a business that does anywhere between $1-10 million a year in annual revenue?

If they’re honest with themselves, most founders are very happy with the latter.

You're almost certainly profitable, can pay yourself over $1 million a year, and can sell the company for $20-40 million. That is life-changing for 99% of us.

However, founders looking to build companies like Uber or Coinbase aren’t primarily motivated by money. They want to create something huge. If that's you, and if the business you're working on now has the potential to be that kind of business, then it makes sense to try raising pre-revenue.

For everyone else? Go get some revenue first.

4 Ways to De-Risk Your Startup Without Revenue

At the pre-seed stage, investors are looking to de-risk two things: the idea and the founding team. They want to ensure that the team has an idea that is scalable and is the right team to build and execute on said idea.

Establishing credibility as a founding team is usually achieved by having the relevant background or education, as mentioned above for the un-average founder. But if you don't have those credentials, you have to prove credibility in other ways.

The best way is… You guessed it… revenue.

But if you've determined that you're in that rare category that needs to raise pre-revenue, here are four ways to get investor attention:

1. Build a Great Team

Fxyer.AI is an AI virtual assistant. The founding team actually built and scaled an agency that provided virtual assistants to professionals in the UK. They scaled it to £5M in ARR in 7 years and grew to become the largest EA staffing agency in the country.

This is the type of deep expertise that VCs often seek. They were able to leverage seven years of knowledge and understanding to create a product that provides people with an always-on virtual assistant at a fraction of the cost of a traditional virtual assistant.

If you're going to raise pre-revenue, having a team with this level of industry expertise would be enough to convince investors that you're worth funding even before you've made a single dollar.

2. Get a BUNCH of Users

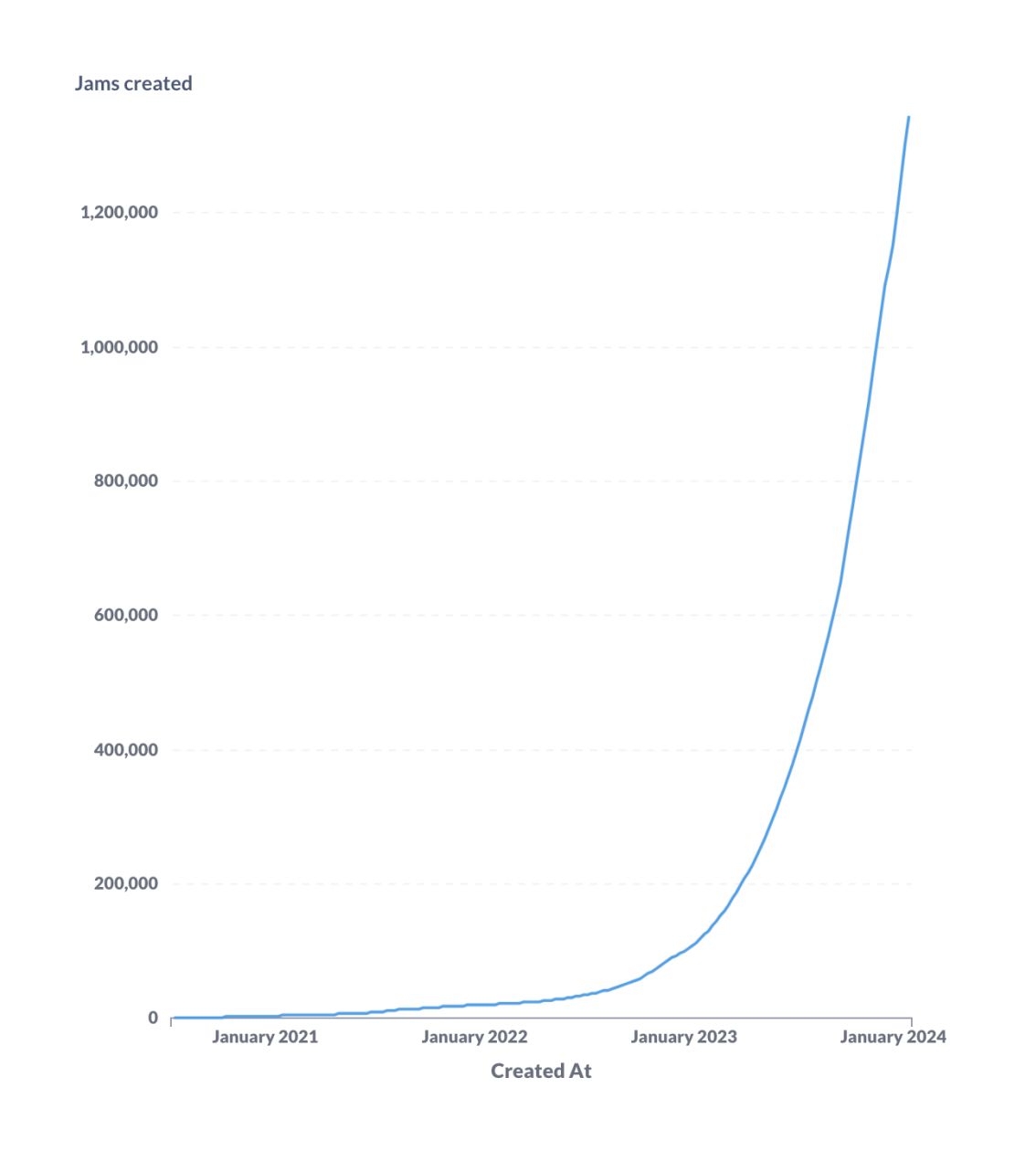

Jam.dev is a tool that helps users capture bugs directly from their Chrome browser. The company raised a $10M Series A in February 2024, and the tool was entirely free because their goal was to acquire a large number of users and then generate revenue.

They had 75,000 users who were submitting over 200,000 jams every month, and they could show impressive growth:

Jam.dev’s growth chart for product usage. If you have a chart that looks like this, then you might have enough to raise without revenue.

Many of these users had raving reviews of Jam, and that was enough to convince investors that the product had become so sticky and irreplaceable in their users’ core workflows that when it came time to turn on pricing and ask people to pay for it, they would be willing to do so.

I assume that the team also had user surveys or maybe a couple of beta-paying customers for the elevated version of Jam, but the point stands. If you have a lot of free users who love your product, that’s something that an investor can’t ignore.

3. Build Hype

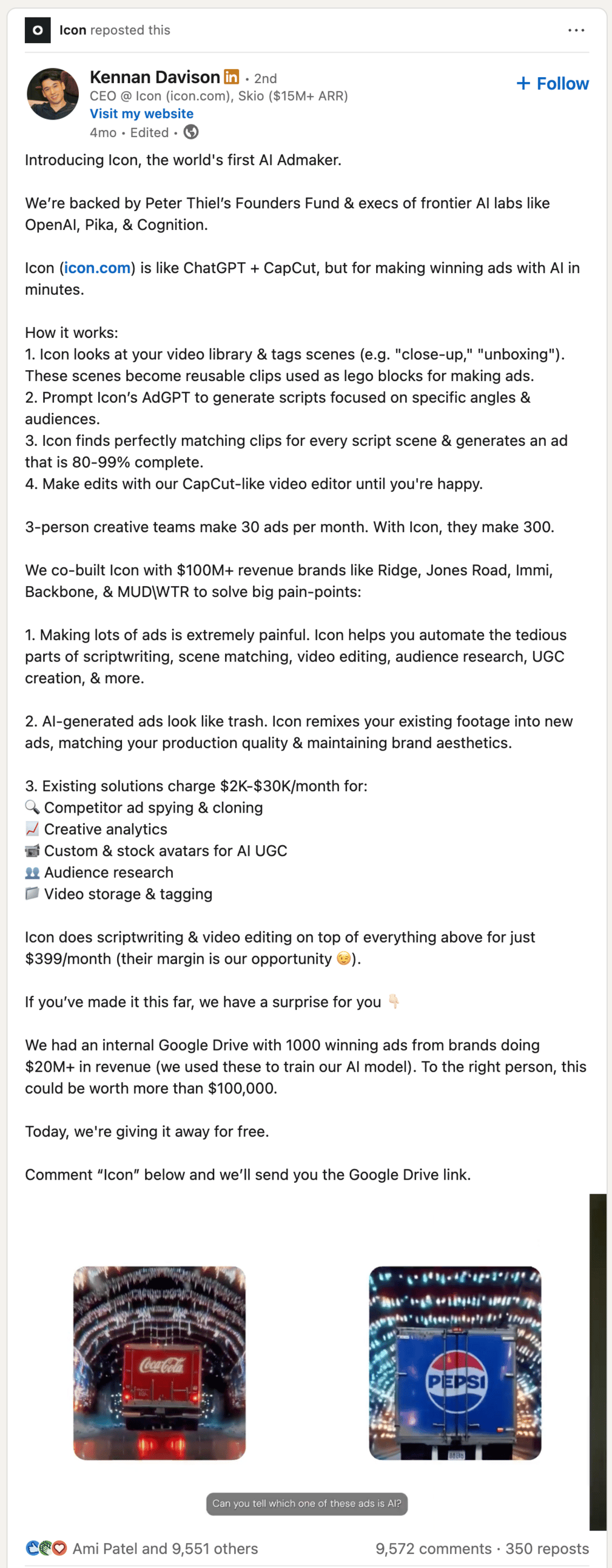

ICON is a company that helps businesses create ad copy and content using AI much faster and cheaper. The company launched masterfully with a viral video on LinkedIn showing people using the product.

ICON’s launch post on LinkedIn.

Now, ICON was able to achieve virality probably because they had venture capital money to invest in their video content and launch.

However, VCs are bandwagoners, and if you can create hype and virality around your company before securing funding and getting people excited about what you're building, you can raise some money.

That could look like:

A series of viral TikTok videos

A couple of days of people talking about your product on Twitter

A successful Product Hunt launch

A social media contest that gets a lot of interaction

This is probably the hardest method because virality is often more a matter of luck than anything else; however, a company that reaches a certain level of virality can raise money simply because venture capitalists don’t want to miss out.

4. Join an Accelerator

Pretty straightforward. Accelerators invest at the earliest stage, so it can be a quick path to funding even if you don’t have revenue.

If you're going to take the accelerator route, target accelerators that offer a substantial check. A $500k investment from an accelerator could turn into $500k in ARR, which, if you’re lean and smart, could make you profitable with high-growth.

At that point, the question is: "Do you even need to raise again?"

If it’s helpful, here are some accelerators that invest $500k+ in their companies:

Y Combinator - Invests in: Early-stage startups across all sectors, including software, hardware, biotech, healthcare, fintech, consumer, and enterprise.

Neo Incubator - Invests in: High-potential solo founders and teams developing technology-driven startups in a wide range of industries.

Greylock Edge - Invests in: Exceptional founders at any stage (including pre-idea), with a focus on technology startups aiming for large-scale impact.

SOSV - Invests in: Startups in specialized sectors like hardware or blockchain through various accelerator programs.

The Irony

None of these methods is a particularly easy or effective alternative for simply generating revenue.

For example, if you don't already have the deep industry expertise that Fxyer has, you're not about to spend years getting it before you go out to try to raise money. Or, if you pursue social media fame for your company, that's really hard to predict and not something you can manufacture.

And that’s the point.

In most cases, it's actually easier to get traction in the form of revenue than it is for you to raise money without having revenue.

The Bottom Line

For 95% of founders, the best way to raise money is to have a lot of money coming in, so much so that you don't actually need the money you're raising. However, if you have the conviction to know that money is the only thing standing between you and serious revenue, then you'd better have something else to attract investors with.

If you’re trying to raise pre-revenue, here's my challenge to you: before you spend months building a team with deep expertise, chasing viral moments, or applying to accelerators, ask yourself honestly whether you've exhausted every possible way to generate even $1 in revenue. Because if you can figure out how to make $1, you can probably figure out how to make $1,000. And if you can make $1,000, you're well on your way to making the case for investment based on traction rather than potential.

The companies I mentioned that successfully raised pre-revenue had something extraordinary to offer investors. If you don't have something extraordinary, focus on building something that people will pay for. That's extraordinary enough.

Catch you next week,

Toby